Load Balancing Logstash With Redis

After yesterday’s post about load balancing logstash with AMQP and RabbitMQ, I got to thinking that it might be useful to show a smilar pattern with other inputs and outputs. To me this, is the crux of what makes Logstash so awesome. Someone asked me to describe Logstash in one sentence. The best I could come up with was:

{% blockquote %} Logstash is a unix pipe on steroids {% endblockquote %}

I hope this post helps you understand what I meant by that

Revisiting our requirements and pattern

If you recall from the post yesterday, we had the following ‘requirements’:

- No lost messages in transit/due to inputs or outputs.

- Shipper only configuration on the source

- Worker based filtering model

- No duplicate messages due to transit mediums (i.e. fanout is inappropriate as all indexers would see the same message)

EDIT

Originally our list stated the requirements as No lost messages and No duplicate messages. I’ve amended those with a slight modification to closer reflect the original intent. Please see comment from Jelle Smet here for details. Thanks Jelle!

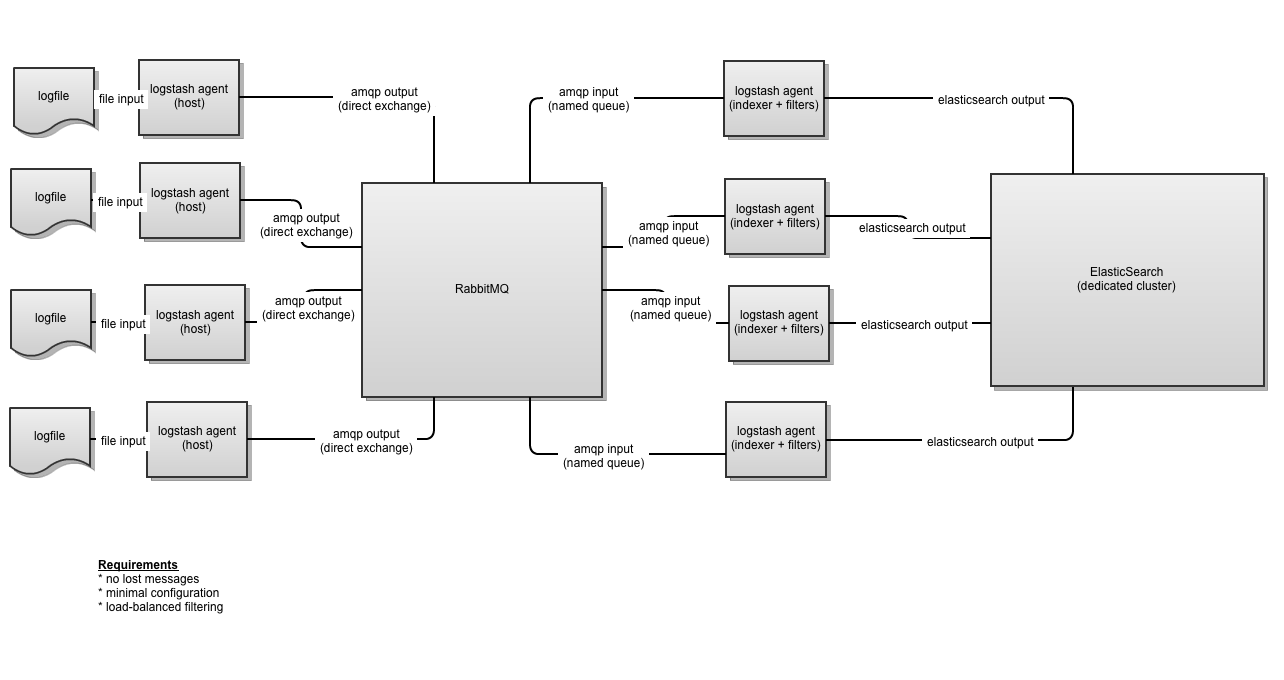

Our design looked something like this:

One of the reasons that post was so long was that AMQP is a complicated beast. There was quite a bit of dense frontloading I had to do to cover AMQP before we got to the meat. We’re going to take that same example, and swap out RabbitMQ for something a bit simpler and achieve the same results.

Quick background on Redis

Redis is commonly lumped in with a group of data storage technologies called NoSQL. Its name is short for “REmoteDIctionaryServer”. It typically falls into the “key/value” family of NoSQL. Several things set Redis apart from most key/value systems however:

- “data types” as values

- native operations on those data types

- atomic operations

- built-in PUB/SUB subsystem

- No external dependencies

Data types

I’m not going to go into too much detail about the data types except to list them and highlight the one we’ll be leveraging. You can read more about them here

- Strings

- Lists*

- Sets

- Hashes

- Sorted Sets

How Logstash uses Redis

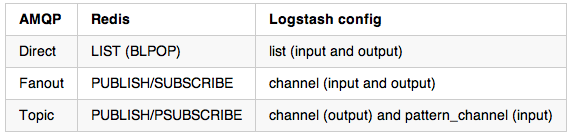

Looking back at our AMQP example, we note three distinct exchange types. These are mapped to the following functionality in Redis (and Logstash data_type config for reference):

This is a somewhat over simplified list. In the case of a message producer, mimicing direct exchanges is done by writing to a Redis list while consumption of that is done via the Redis command BLPOP*. However mimicing the fanout and topic functionality is done strictly with the commands PUBLISH*, SUBSCRIBE* and PSUBSCRIBE*. It’s worth reading each of those for a better understanding.

Oddly enough, the use of Redis as a messaging bus is something of a side effect. Redis supported lists that are auto-sorted by insert order. The POP command variants allowed single transaction get and remove of the data. It just fit the use case.

The configs

As with our previous example, we’re going to show the configs needed on each side and explain them a little bit.

Client-side/Producer

input { stdin { type => "producer"} }

output {

redis {

host => 'localhost'

data_type => 'list'

key => 'logstash:redis'

}

}

data_type

This is where we tell Logstash how to send the data to Redis. In the case, again, we’re storing it in a list data type.

key

Unfortunately, key means different things (though with the same effect) depending on the data_type being used. In the case of a list this maps cleanly to the understanding of a key in a key/value system. It’s common in Redis to namespace keys with a : though it’s entirely unneccesary.

As an aside, when using key on channel data type, this behaves like the routing key in AMQP parlance with the exception of being able to use any separator you like (in other words, you can namespace with .,:,:: whatever).

Indexer-side/Consumer

input {

redis {

host => 'localhost'

data_type => 'list'

key => 'logstash:redis'

type => 'redis-input'

}

}

output {stdout {debug => true} }

data_type

This needs to match up with the value from the output plugin. Again, in this example list.

key

In the case of a list this needs to map EXACTLY to the output plugin. Following on to our previous aside, for data_type values of channel input, the key must match exactly while pattern_channel can support wildcards. Redis PSUBSCRIBE wildcards actually much simpler than AMQP ones. You can use * at any point in the key name.

Starting it all up

We’re going to simplify our original tests a little bit in the interest of brevity. Showing 2 producers and 2 consumers gives us the same benefit as showing four of each. Since we don’t have the benefit of a pretty management interface, we’re going to use the redis server debug information and the redis-cli application to allow us to see certain management information.

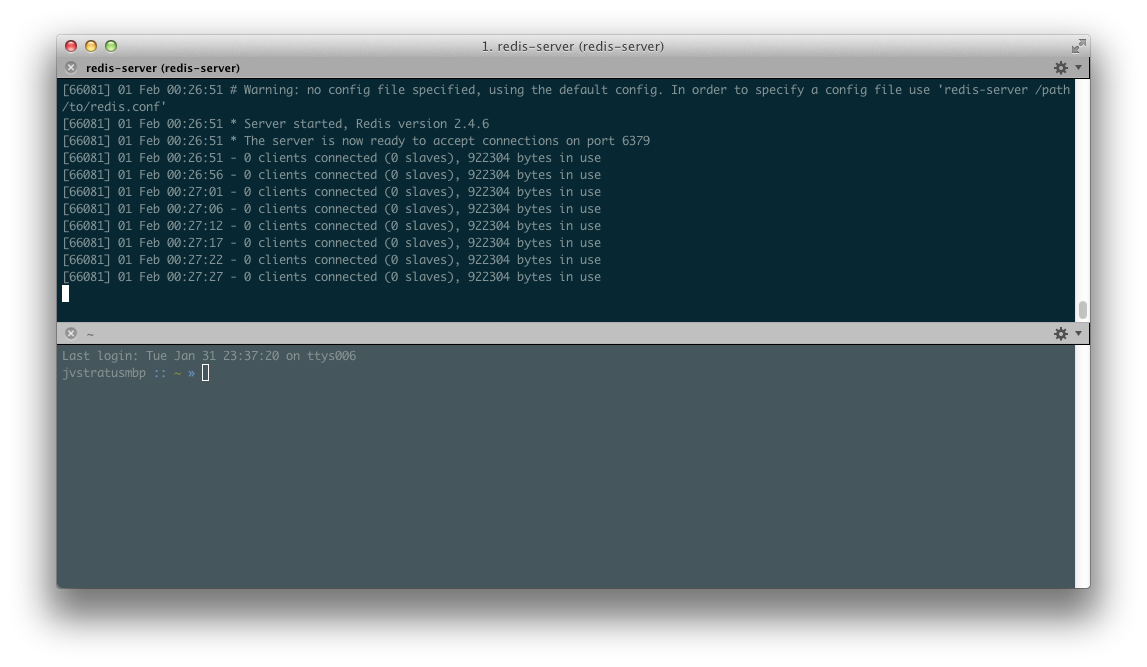

redis-server

Start the server with the command redis-server I’m running this from homebrew but you literally build Redis on any machine that has make and a compiler. That’s all you need. You can even run it straight from the source directory:

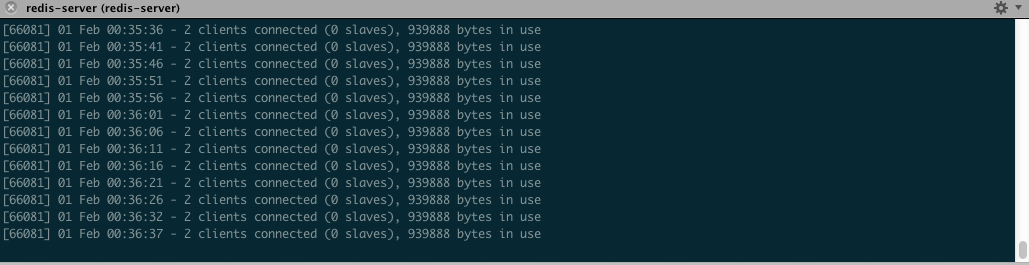

You’ll notice that the redis server is periodically dumping some stats - number of connected clients and the amount of memory in use.

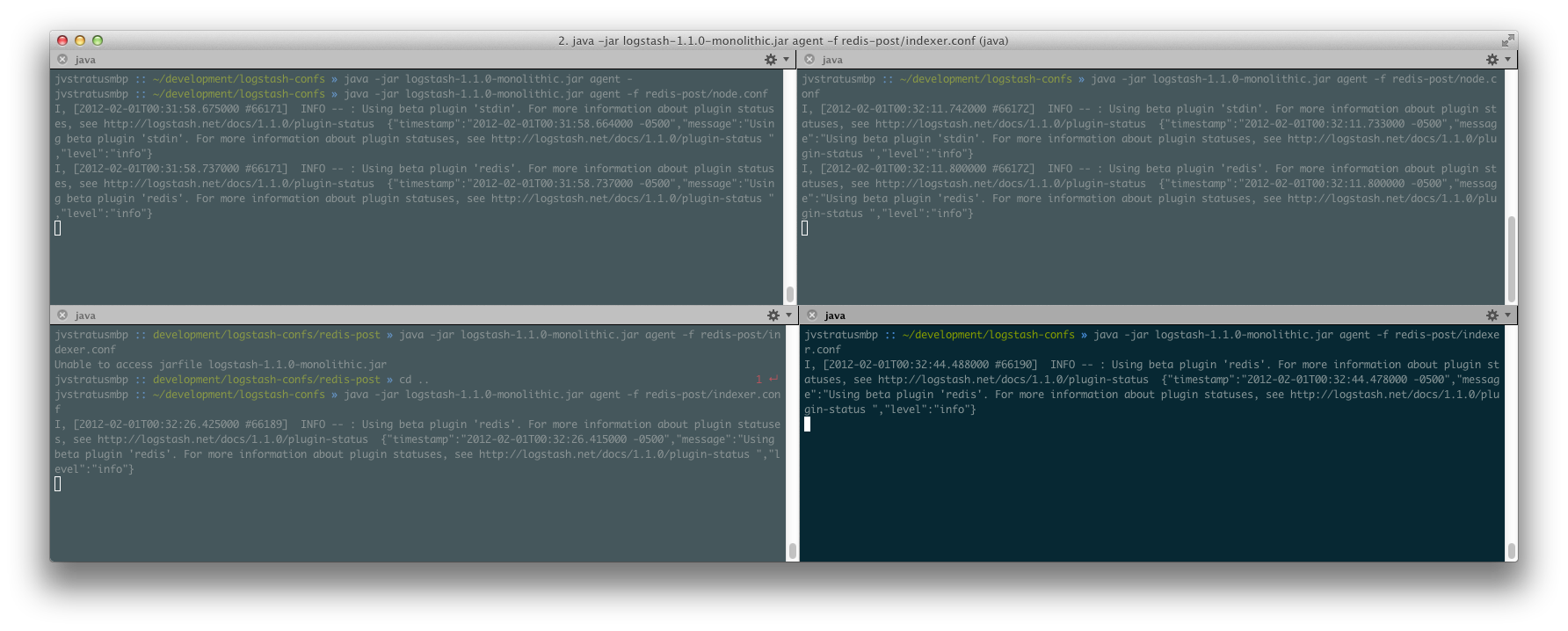

Starting the logstash agents

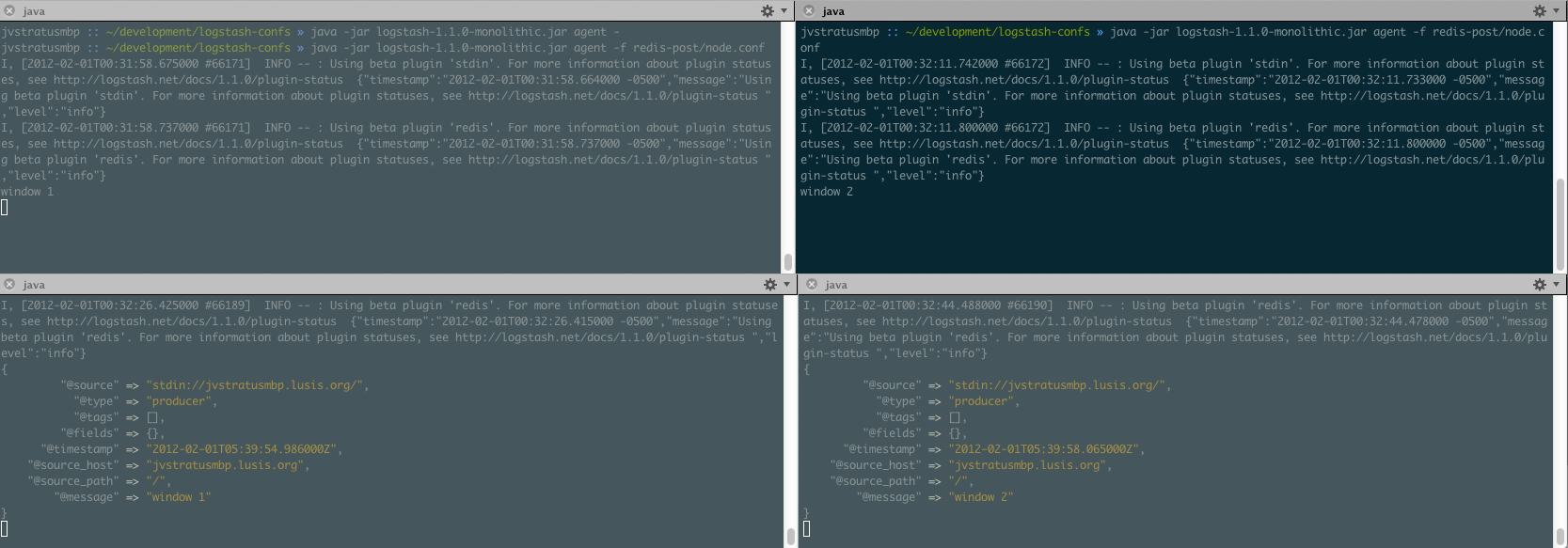

We’re going to start two producers (redis output) and two consumers (redis input):

Back in our redis-server window, you should now see two connected clients in the periodic status messages. Why not four? Because the producers don’t have a persistent connection to Redis. Only the consumers do (via BLPOP):

Testing message flow

As with our previous post, we’re going to alternate messages between the two producers. In the first producer, we’ll type window 1 and in the second window 2. You’ll see the consumers pick up the messages:

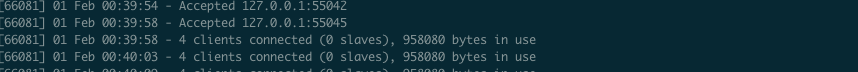

If you look over in the redis-server window, you’ll also see that our client count went up to four. If we were to leave these clients alone, eventually it would drop back down to two.

Feel free to run the tests a few times and get a feel for message flow.

Offline consumers

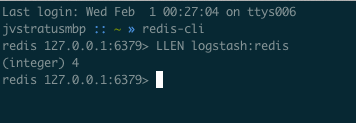

This is all well and good but as with the previous example, we want to test how this configuration handles the case of consumers going offline. Shut down the two indexer configs and let’s verify. To do this, we’re going to also open up a new window and run the redis-cli app. Technically, you don’t even need that. You can telnet to the redis port and just run these commands yourself. We’re going to use the LLEN command to get the size of our “backlog”.

In the producer windows, type a few messages. Alternate between producers for maximum effect. Then go over to the redis-cli window and type LLEN logstash:redis. You should see something like the following (obviously varied by how many messages you sent):

You’ll also notice in the redis server window that the amount of memory in use went up slightly.

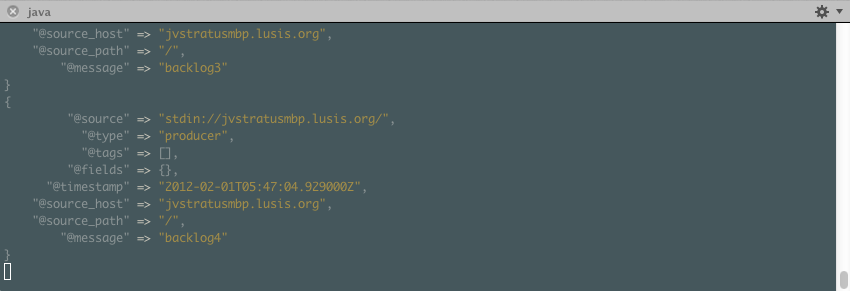

Now let’s start our consumers back up and ensure they drain (and in insert order):

Looks good to me!

Persistence

You might have noticed I didn’t address disk-based persistence at all. This was intentional. Redis is primarily a memory-based store. However it does have support for a few different ways of persisting to disk - RDB and AOF. I’m not going to go into too much detail on those. The Redis documentation does a good job of explaining the pros and cons of each. You can read that here.

Wrap up

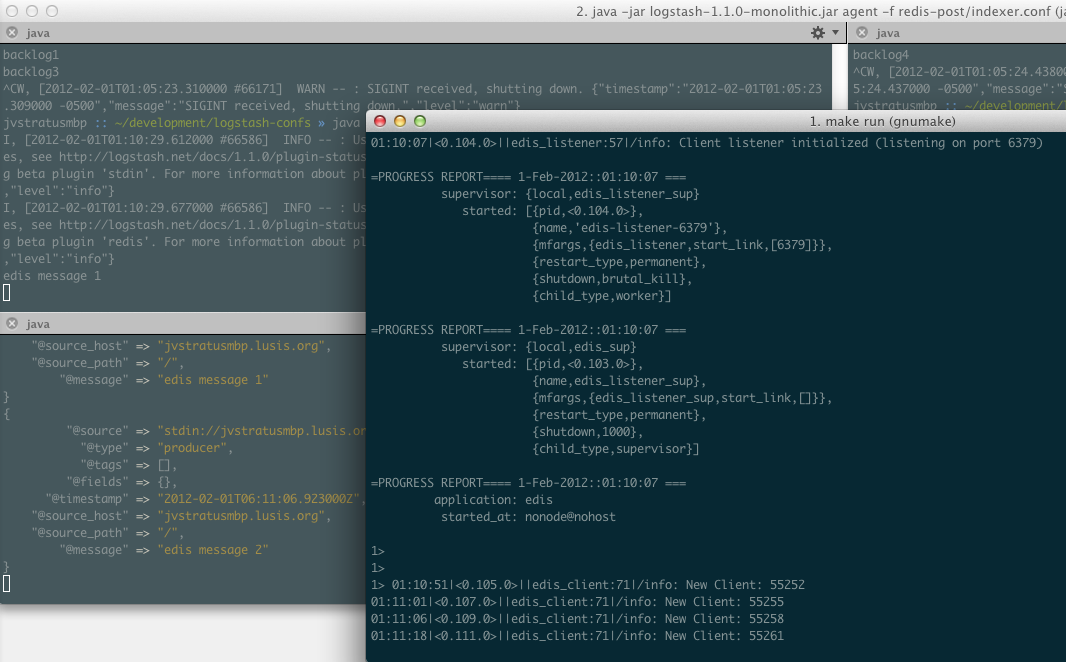

One thing that’s important to note is that Redis is pretty damn fast. The limitation for Redis is essentially memory. However if speed isn’t your primary concern, there’s an interesting alpha project called edis worth investigating. It is a port of Redis to Erlang. Its primary goal is better persistence for Redis. For this post I also tested Logstash against edis and I’m happy to say it works:

I hope to do further testing with it in the future in a multinode setup.

Part three

I’m also working on a part three in this “series”. The last configuration I’d like to show is doing this same setup but using 0mq as the bus. This is going to be especially challenging since our 0mq support is curretly ‘alpha’-ish quality. Beyond that, I plan on doing a similar series using pub/sub patterns. If you’re enjoying these posts, please comment and let me know!